WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW!

- Mastering Shooting modes (including priority modes and full manual)

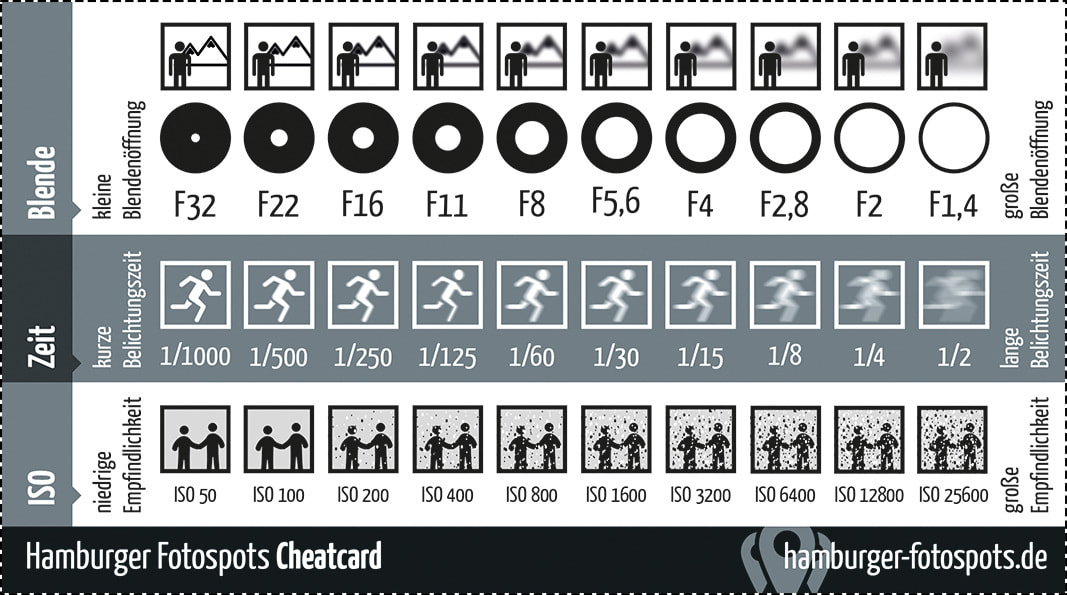

- Understanding ISO

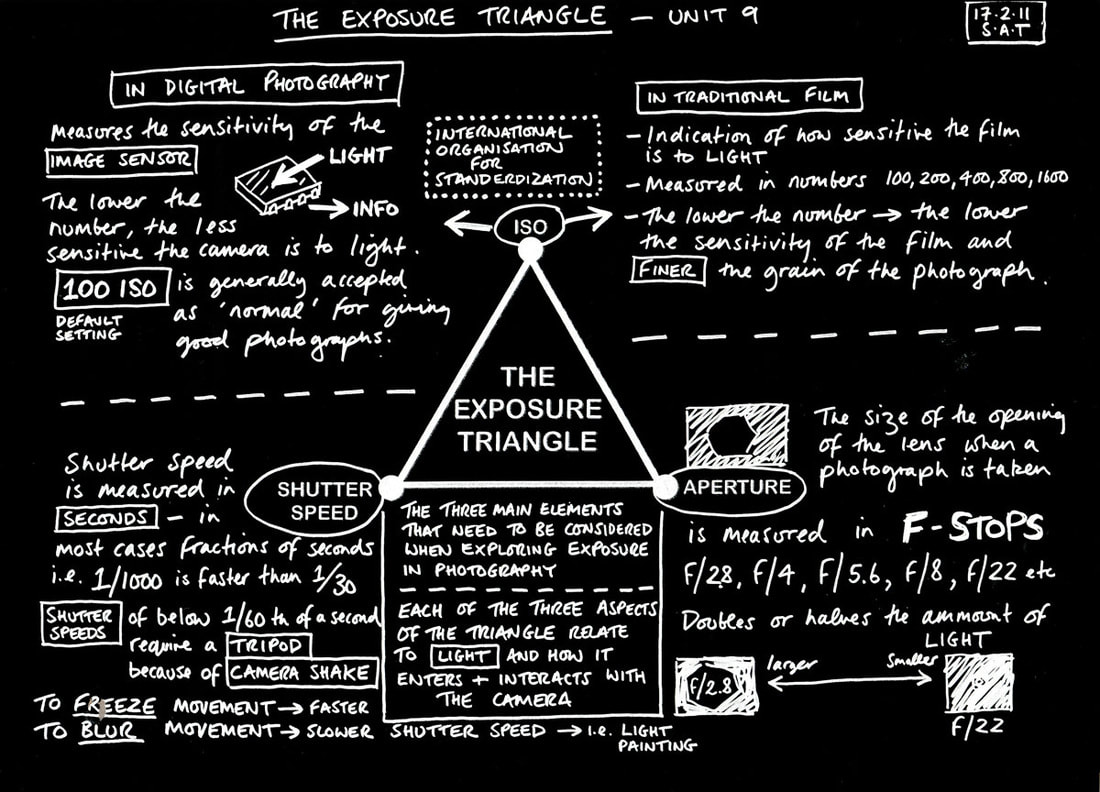

- Learning the ‘exposure triangle’

1. Aperture

Aperture is one of the most important aspects of photography as it directly influences the depth of field – that is, the amount of an image that is in focus. A large depth of field (achieved by using a small aperture (large f-number)) would mean that a large distance within the scene is in focus, such as the foreground to the background of the landscape below.

An aperture of f/13 was used here to give a large depth of field, ensuring that the whole image, from the foreground grasses to the background mountains. was sharp

Whereas a shallow depth of field (achieved by using a large aperture (small f-number)) would produce an image where only the subject is in sharp focus, but the background is soft and out of focus. This is often used when shooting portraiture or wildlife, such as the image below, to isolate the subject from the background:

A large aperture of f/4.5 was used to capture this water vole, against a soft, out of focus background

SHOOTING MODES

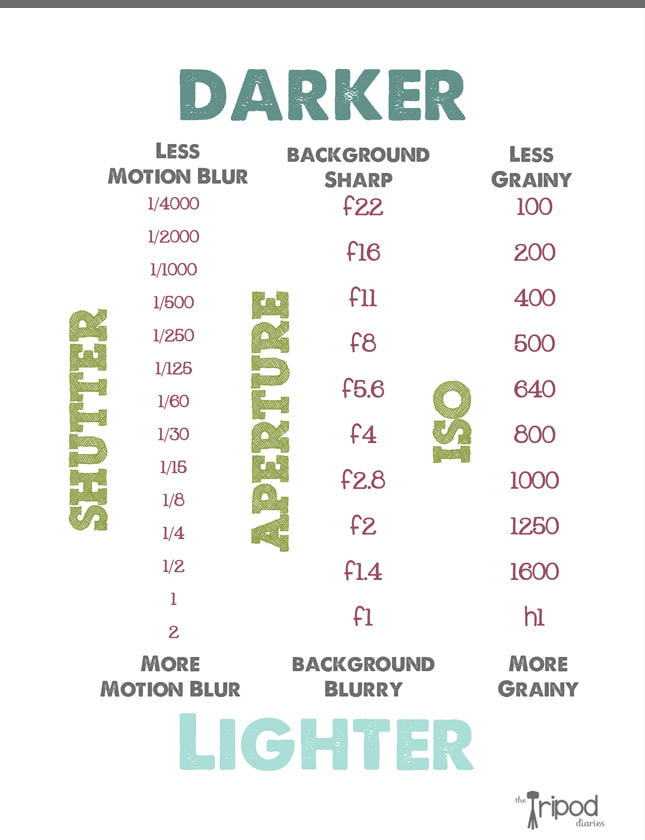

The best place to start is with shooting modes. The shooting modes will most likely be found on a dial labelled with ‘auto, Av, Tv, P, M’ and maybe more. Selecting a shooting mode will determine how your camera behaves when you press the shutter, for example, when ‘auto’ is selected, the camera will determine everything to do with the exposure, including the aperture and shutter speed. The other modes, ‘Av, Tv, P, M’, are there to give you control:

Don’t worry if your mode dial looks a little different; different manufacturers use different abbreviations for the shooting modes. Your mode dial may have the letters ‘A, S, P, M’ (instead of Av, Tv, P, M), yet they all function in the same way. Below, I have given each abbreviation for the given mode.

The best place to start is with shooting modes. The shooting modes will most likely be found on a dial labelled with ‘auto, Av, Tv, P, M’ and maybe more. Selecting a shooting mode will determine how your camera behaves when you press the shutter, for example, when ‘auto’ is selected, the camera will determine everything to do with the exposure, including the aperture and shutter speed. The other modes, ‘Av, Tv, P, M’, are there to give you control:

Don’t worry if your mode dial looks a little different; different manufacturers use different abbreviations for the shooting modes. Your mode dial may have the letters ‘A, S, P, M’ (instead of Av, Tv, P, M), yet they all function in the same way. Below, I have given each abbreviation for the given mode.

Aperture Priority (Av or A)

Aperture priority can be thought of as a ‘semi-automatic’ shooting mode. When this is selected, you as the photographer set the aperture and the camera will automatically select the shutter speed. So what is aperture and when would you want to control it?

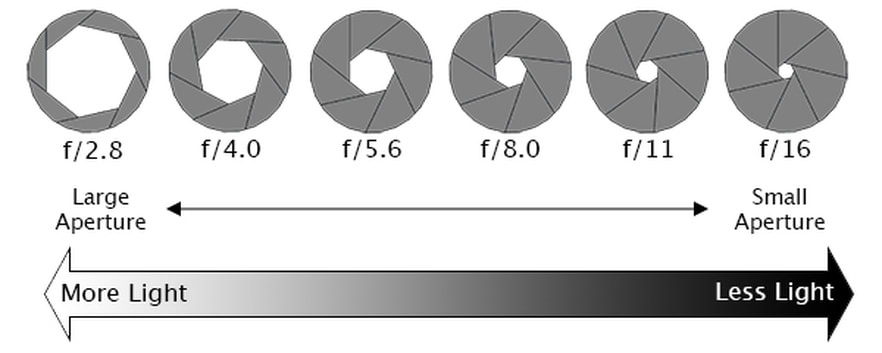

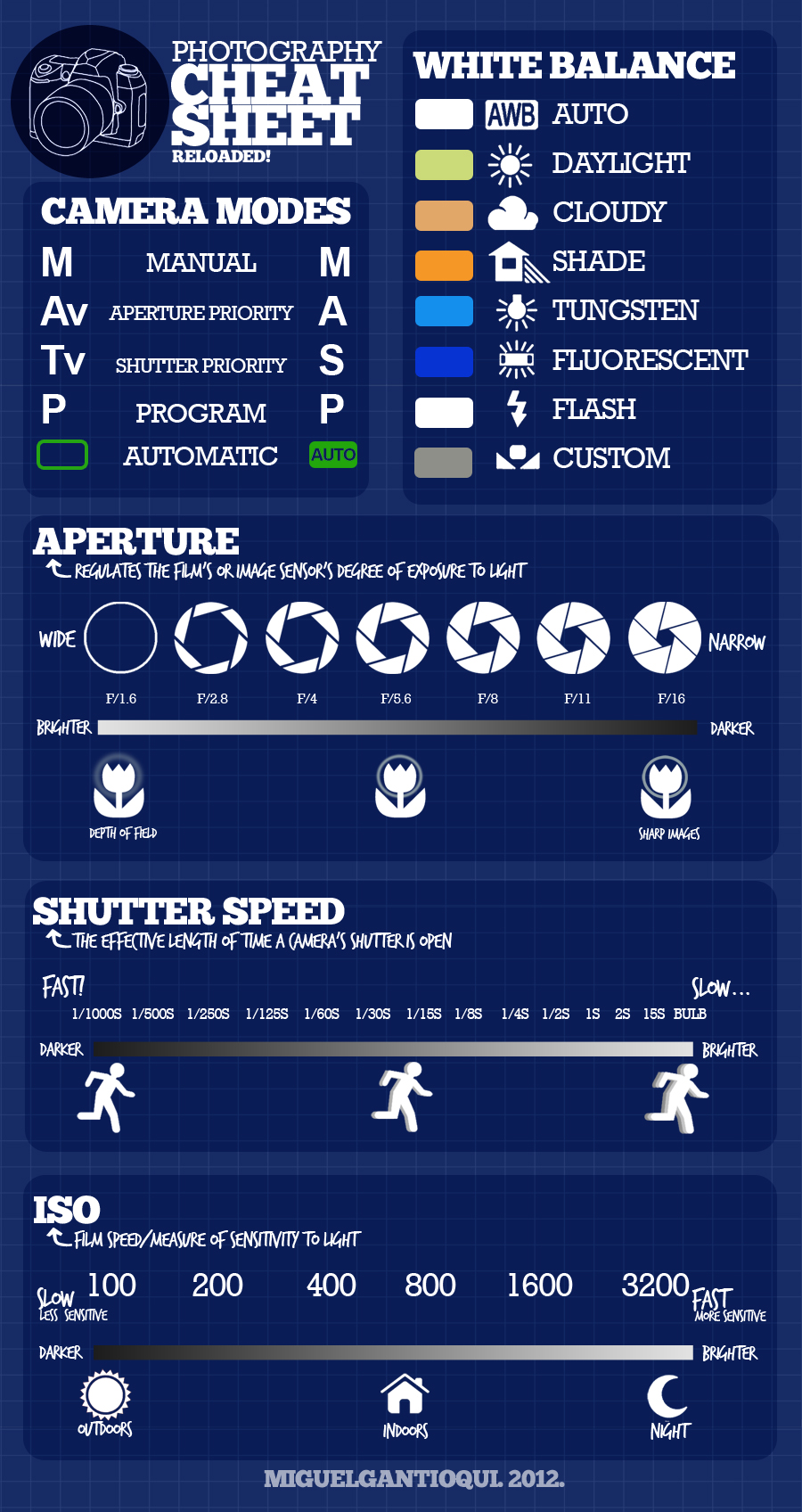

The aperture is the size of the opening in the lens through which light is allowed to pass whenever the shutter is opened – the larger the aperture, the more light passes through.

The aperture is measured in ‘f-stops’ and is usually displayed using an ‘f-number’, e.g. f/2.0, f/2.8, f/4.0, f/5.6, f/8.0 etc, which is a ratio of focal length over diameter of the opening. Therefore, a larger aperture (a wider opening) has a smaller f-number (e.g. f/2.0) and smaller aperture (a narrower opening) has a larger f-number (e.g. f/22). Reducing the aperture by one whole f-stop, e.g. f/2.0 to f2/8 or f/5.6 to f/8.0, halves the amount of light entering the camera.

So when using aperture priority, you can get complete control over your depth of field, whilst the camera takes care of the rest.

Aperture priority can be thought of as a ‘semi-automatic’ shooting mode. When this is selected, you as the photographer set the aperture and the camera will automatically select the shutter speed. So what is aperture and when would you want to control it?

The aperture is the size of the opening in the lens through which light is allowed to pass whenever the shutter is opened – the larger the aperture, the more light passes through.

The aperture is measured in ‘f-stops’ and is usually displayed using an ‘f-number’, e.g. f/2.0, f/2.8, f/4.0, f/5.6, f/8.0 etc, which is a ratio of focal length over diameter of the opening. Therefore, a larger aperture (a wider opening) has a smaller f-number (e.g. f/2.0) and smaller aperture (a narrower opening) has a larger f-number (e.g. f/22). Reducing the aperture by one whole f-stop, e.g. f/2.0 to f2/8 or f/5.6 to f/8.0, halves the amount of light entering the camera.

So when using aperture priority, you can get complete control over your depth of field, whilst the camera takes care of the rest.

2: Shutter Speed

Shutter speed is a measure of how long the shutter remains open and thus, how long the sensor is exposed to light. Faster shutter speeds give the sensor less time to collect light and thus, result in a lower exposure. Slower shutter speeds allow more time for the sensor to collect light and result in a higher exposure.

In this case, the reason we might want to use a higher shutter speed is to stop motion, whether that be camera shake or a subject that is moving, allowing us to maintain sharpness. Remember, as long as the shutter is open, the camera is essentially recording the position of elements in the frame; if one of those elements moves, the result will often be undesired blurriness.

Many photographers will argue that this is the most important aspect, saying if your shutter speed isn’t fast enough to give you a sharp image, nothing else will save the image. In general, I agree.

In this case, the reason we might want to use a higher shutter speed is to stop motion, whether that be camera shake or a subject that is moving, allowing us to maintain sharpness. Remember, as long as the shutter is open, the camera is essentially recording the position of elements in the frame; if one of those elements moves, the result will often be undesired blurriness.

Many photographers will argue that this is the most important aspect, saying if your shutter speed isn’t fast enough to give you a sharp image, nothing else will save the image. In general, I agree.

You would use a long shutter speed if you wanted to blur a moving subject, for example water rushing over a waterfall (slower shutter speeds will require you to put the camera on a tripod to ensure the camera is held steady whilst the shutter is open):

Shutter Priority (Tv or S)

Similarly to aperture priority, this is another ‘semi-automatic’ shooting mode, though in this instance, you as the photographer set the shutter speed and the camera will take care of the aperture. The shutter speed, measured in seconds (or more often fractions of a second), is the amount of time the shutter stays open when taking a photograph. The longer the shutter stays open, the more light passes through to the sensor to be captured.

So whilst you worry about what shutter speed you need for a given photograph, the camera will determine the appropriate aperture required to give the correct exposure.

Aperture and shutter priority shooting modes may be semi-automatic, meaning that some may deride their use because they’re not fully manual, however they are incredibly useful modes to shoot in that can give you enough creative control to capture scenes as you envisage them.

Similarly to aperture priority, this is another ‘semi-automatic’ shooting mode, though in this instance, you as the photographer set the shutter speed and the camera will take care of the aperture. The shutter speed, measured in seconds (or more often fractions of a second), is the amount of time the shutter stays open when taking a photograph. The longer the shutter stays open, the more light passes through to the sensor to be captured.

So whilst you worry about what shutter speed you need for a given photograph, the camera will determine the appropriate aperture required to give the correct exposure.

Aperture and shutter priority shooting modes may be semi-automatic, meaning that some may deride their use because they’re not fully manual, however they are incredibly useful modes to shoot in that can give you enough creative control to capture scenes as you envisage them.

Manual (M)

Manual mode is exactly what it sounds like, you are given full control over the exposure determination, setting both the aperture and shutter speed yourself. There will be an exposure indicator either within the viewfinder or on the screen that will tell you how under/over exposed the image will be, however, you are left to change the shutter speed and aperture yourself to ensure you achieve the correct exposure.

Practically Speaking: as a first step to taking your camera off ‘auto’, aperture priority and shutter priority modes offer two very simple ways to start to understand how the different setting impact your images and are a perfect starting place for learning how to use your camera more creatively.

Manual mode is exactly what it sounds like, you are given full control over the exposure determination, setting both the aperture and shutter speed yourself. There will be an exposure indicator either within the viewfinder or on the screen that will tell you how under/over exposed the image will be, however, you are left to change the shutter speed and aperture yourself to ensure you achieve the correct exposure.

Practically Speaking: as a first step to taking your camera off ‘auto’, aperture priority and shutter priority modes offer two very simple ways to start to understand how the different setting impact your images and are a perfect starting place for learning how to use your camera more creatively.

Side 3: ISO

ISO is a measure of how sensitive the sensor of your camera is to light. The term originated in film photography, where film of different sensitivities could be used depending on the shooting conditions, and it is no different in digital photography. The ISO sensitivity is represented numerically from ISO 100 (low sensitivity) up to ISO 6400 (high sensitivity) and beyond, and controls the amount of light required by the sensor to achieve a given exposure

At ‘low’ sensitivities, more light is required to achieve a given exposure compared to high sensitivities where less light is required to achieve the same exposure. To understand this, let’s look at two different situations:

Low ISO numbers

If shooting outside, on a bright sunny day there is a lot of available light that will hit the sensor during an exposure, meaning that the sensor does not need to be very sensitive in order to achieve a correct exposure. Therefore, you could use a low ISO number, such as ISO 100 or 200. This will give you images of the highest quality, with very little grain (or noise).

At ‘low’ sensitivities, more light is required to achieve a given exposure compared to high sensitivities where less light is required to achieve the same exposure. To understand this, let’s look at two different situations:

Low ISO numbers

If shooting outside, on a bright sunny day there is a lot of available light that will hit the sensor during an exposure, meaning that the sensor does not need to be very sensitive in order to achieve a correct exposure. Therefore, you could use a low ISO number, such as ISO 100 or 200. This will give you images of the highest quality, with very little grain (or noise).

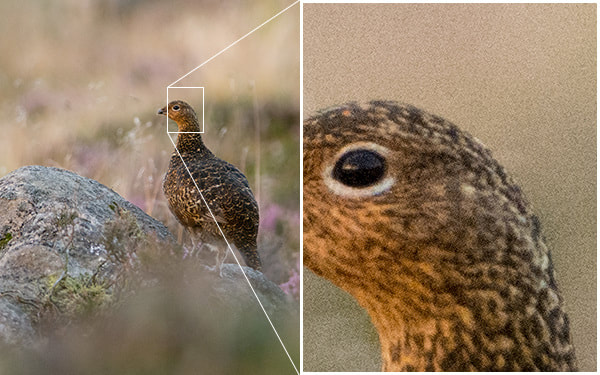

High ISO numbers

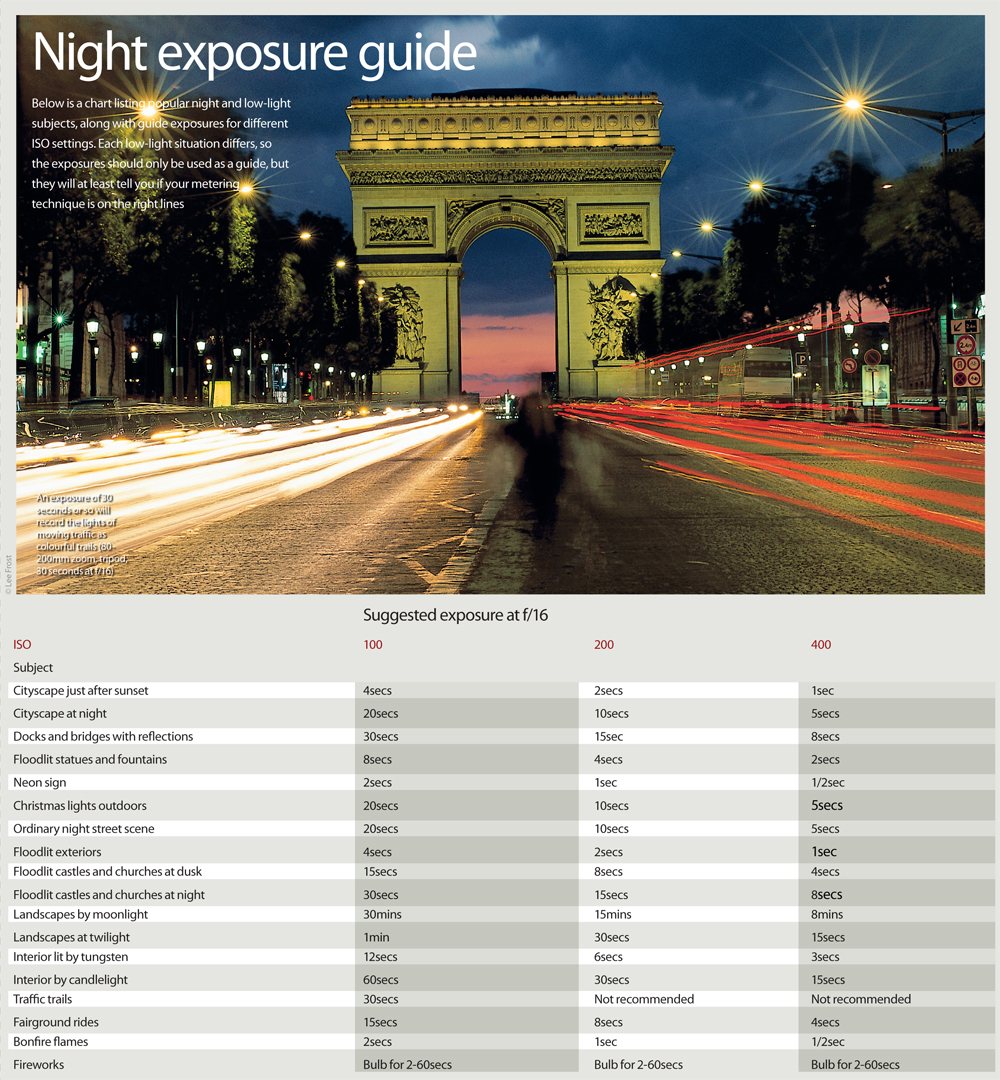

If shooting in low light conditions, such as inside a dark cathedral or museum for example, there is not much light available for your camera sensor. A high ISO number, such as ISO 3200, will increase the sensitivity of the sensor, effectively multiplying the small amount of available light to give you a correctly exposed image. This multiplication effect comes with a side effect of increased noise on the image, which looks like a fine grain, reducing the overall image quality. The noise will be most pronounced in the darker/shadow regions.

If shooting in low light conditions, such as inside a dark cathedral or museum for example, there is not much light available for your camera sensor. A high ISO number, such as ISO 3200, will increase the sensitivity of the sensor, effectively multiplying the small amount of available light to give you a correctly exposed image. This multiplication effect comes with a side effect of increased noise on the image, which looks like a fine grain, reducing the overall image quality. The noise will be most pronounced in the darker/shadow regions.

Practically Speaking: you want to keep the ISO as low as possible, as the lower the ISO, the less noise and the higher the quality of the resulting image. Outside on a sunny day, select ISO200 and see how it goes. If it clouds over, maybe select an ISO between 400-800. If you move indoors, consider an ISO of around 1600 or above (these are approximate starting points).

Most digital SLRs now have an ‘auto-ISO’ function, where the camera sets the ISO depending upon the amount of light in which you are shooting, keeping it as low as possible. Auto-ISO is a very useful tool when starting out with your camera, as it is allows you to define an upper limit i.e. where the images become too noisy such as ISO1600 or 3200, and then forget about it until situations where you specifically want to override the automatic setting, for example if taking landscape images using a tripod, you can afford to use the lowest ISO possible.

Most digital SLRs now have an ‘auto-ISO’ function, where the camera sets the ISO depending upon the amount of light in which you are shooting, keeping it as low as possible. Auto-ISO is a very useful tool when starting out with your camera, as it is allows you to define an upper limit i.e. where the images become too noisy such as ISO1600 or 3200, and then forget about it until situations where you specifically want to override the automatic setting, for example if taking landscape images using a tripod, you can afford to use the lowest ISO possible.

Completion of the Exposure Triangle

It’s important to note that aperture, shutter speed and ISO are all part of the ‘exposure triangle’. They all control either the amount of light entering the camera (aperture, shutter speed) or the amount of light required by the camera (ISO) for a given exposure.

Therefore, they are all linked, and understanding the relationship between them is crucial to being able to take control of your camera. A change in one of the settings will impact the other two. For example, considering a theoretical exposure of ISO400, f/8.0, 1/10th second. If you wanted to reduce the depth of field, and decided to use an aperture of f/4.0, you would be increasing the size of the aperture by two whole f/stops, therefore increasing the amount of light entering the camera by a factor of 4 (i.e. increasing by a factor of 2, twice). Therefore, to balance the exposure, you could do the following:

Therefore, they are all linked, and understanding the relationship between them is crucial to being able to take control of your camera. A change in one of the settings will impact the other two. For example, considering a theoretical exposure of ISO400, f/8.0, 1/10th second. If you wanted to reduce the depth of field, and decided to use an aperture of f/4.0, you would be increasing the size of the aperture by two whole f/stops, therefore increasing the amount of light entering the camera by a factor of 4 (i.e. increasing by a factor of 2, twice). Therefore, to balance the exposure, you could do the following:

EXAMPLES

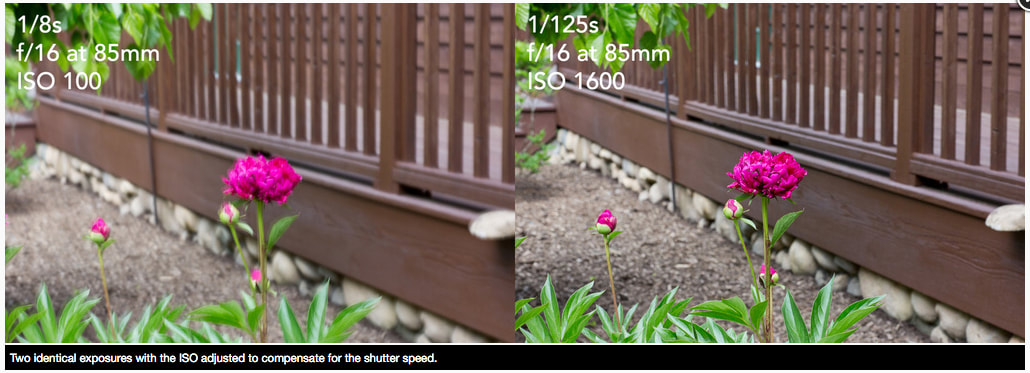

Notice how every time I reduced the aperture by one stop, I also decreased the shutter speed by one stop; thus, the overall exposure is the same in each shot. Nonetheless, the differences are quite noticeable. In the f/1.4 example, the flower in the center of the frame is quite prominent and isolated; the busy deck railing melts away rather nicely. By f/8, my depth of field is much bigger; the deck railing is much more prominent and it isn't clear what the focus of the image is. Also, in the last two images, I'm really beginning to risk camera shake by shooting at speeds slower than the reciprocal of my focal length (I tend to err on the conservative side of that classic rule anyway), 1/85s. Luckily, I've been working on reducing my caffeine intake, so my hands appear to be a bit steadier than in the past.

Notice how in this set, I simply couldn't keep the camera still enough for an exposure of 1/8s at 85mm. Even caffeine-free, that's tough to pull off. By increasing the shutter speed 4 stops to a reasonable speed for that focal length and compensating by increasing the ISO 4 stops, I was able to get a sharp image with a large depth of field. Remember, a high ISO, sharp image is always preferable to a low ISO, blurry image.

Knowing the exposure triangle is crucial to getting technically correct images and controlling your composition. Put you camera in manual mode and begin experimenting with the three variables. You'll have an intuitive grasp of them before you know it.

( taken from https://fstoppers.com/education/exposure-triangle-understanding-how-aperture-shutter-speed-and-iso-work-together-72878)

Knowing the exposure triangle is crucial to getting technically correct images and controlling your composition. Put you camera in manual mode and begin experimenting with the three variables. You'll have an intuitive grasp of them before you know it.

( taken from https://fstoppers.com/education/exposure-triangle-understanding-how-aperture-shutter-speed-and-iso-work-together-72878)

FORMATIVE ASSIGNMENT

Create a composition with a subject in the foreground as your primary interest.

- You will be submitting 6 versions of the same composition moving along the exposure triangle.

- Each image will need to have differing depth of field.

- All 6 image must be properly exposed

- All 6 images must be labeled with iso, aperture (f) and Shutter Speed

- You will be submitting 6 versions of the same composition moving along the exposure triangle.

- Each image will need to have differing depth of field.

- All 6 image must be properly exposed

- All 6 images must be labeled with iso, aperture (f) and Shutter Speed